As you probably know by now, aptitudes are innate and there is nothing you can do to acquire one you do not have. But some still wonder about how someone who knows a lot can be “limited” by their aptitudes.

Career test publishers and administrators recognize that knowledge has an effect on aptitude use and take this relationship into account through the measurement of vocabulary. Because test publishers have access to huge amounts of statistical data, they have been able to find that a large vocabulary is usually present in a successful professional of any field.

That is, across all career fields, the most successful test-takers have a large English vocabulary. Let’s look at how vocabulary is measured, how it affects our aptitudes, and, most importantly, what you can do to take the greatest advantage of your aptitudes through vocabulary.

Vocabulary as a measure of knowledge

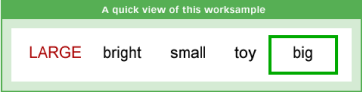

Johnson O’Connor explains the measurement of vocabulary in the following quote: “English vocabulary is measured in essentially two different ways. How many words do you recognize and understand in print? How many words do you use in conversation? Each of these questions will yield a different answer because people understand many more words than they ever use in conversation. We measure English vocabulary primarily through untimed multiple-choice recognition tests. We ask you to decide which of the five words or phrases is closest in meaning to the test word. This gives us a good idea of the words you recognize and understand”

The Highlands Ability Battery uses a test like this to determine how precise and large your vocabulary is

“We have many different vocabulary tests, at all levels of difficulty. We convert raw scores on these tests to a vocabulary scale, covering all the tests. This vocabulary scale, which runs from 40 to 225, tells us your vocabulary level; your percentile score, in the next column, tells us how this level compares to that of other people we have tested of the same age. Our testing population is well above average in vocabulary compared to the general population. Your percentile score could be considerably higher if we were to compare you with the entire United States population of your age.

“If you are planning to go to college or have been to college, however, and are aiming towards a managerial or professional career, we feel that a comparison with our testing population will give you a good idea of how your vocabulary rates with the kind of people with whom you will be competing.”

Age and Vocabulary

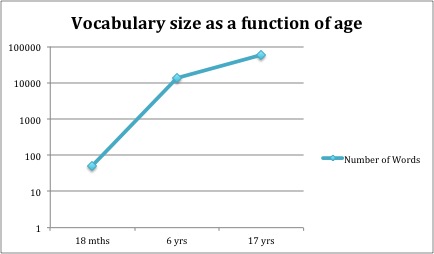

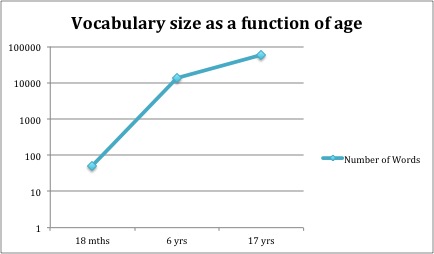

Vocabulary keeps increasing with age. A 30-year-old who is low in vocabulary compared to others in the same age range will still have a higher vocabulary scale score than the highest vocabulary 10-year-old. This is because knowledge builds up throughout life. An important point to keep in mind about your score in vocabulary is that you are only compared with test-takers your age, not by those outside of your age range. Your score will reflect how you rank compared with your peers.

The older a person is, generally the more words they know. You are tested within an age bracket and compared to those only in your same age range.

Knowledge and Aptitudes

A strong vocabulary is an essential tool for gaining knowledge, and your vocabulary level will give you an idea of how far you can go with your aptitudes. A small vocabulary limits the use that you can make of your natural abilities. A large vocabulary does not guarantee success; it simply makes the full use of one’s aptitudes possible. The most obvious advantage of having a good vocabulary is that it helps in school. English vocabulary correlates more highly with school grades than any other test we administer. A low-vocabulary student may have difficulty succeeding in school; high-vocabulary students, on the other hand, are more likely to get the best training possible, which impacts the use of their aptitudes.

Vocabulary is important in work as well, and not just in verbal fields such as law or journalism. In a work environment, where co-workers tend to have a similar pattern of aptitudes, the ones who go the furthest will normally be those who have the greatest knowledge of their field and the widest vocabulary, which helps them think and express themselves clearly. Thus we have found that presidents of major corporations are among the highest in vocabulary of any group we have tested, even though some of these executives have had little formal education.

Two Types of Vocabulary

We emphasize the importance of both a large and a precise vocabulary. A large vocabulary broadens your knowledge of the world. As children learn words like “desk” or “run” or “friend,” they increase the number of things, actions, and ideas they understand. This process never stops, although some people take it much further than others. The high-vocabulary person simply has a wider range of general knowledge.

A precise vocabulary generally accompanies a large vocabulary, although the two are distinct. Having a precise vocabulary means that you understand clearly and well the words you use. Thus the child may know both “run” and “walk,” but not be sure of the difference, and as a result may sometimes use the words inaccurately until sure of them. People often think they know a word but in reality have some misunderstanding of it. Thus someone might suppose that something “shabby” has to be “old,” or that something “inexpensive” must be “inferior.” We feel that a large and precise vocabulary indicates a broad, general knowledge, which is valuable for its own sake.

How to Increase your vocabulary

Your vocabulary increases as you broaden your knowledge of different subjects. This is particularly true during the years you are in school. But if your vocabulary percentile is low now, the natural increase in vocabulary will not be enough to give you a relatively high vocabulary when you are older. Everyone else your age will be learning more words, too. Your vocabulary scale score will gradually increase, but your percentile will remain the same. To catch up, you must add to this natural growth with active word study.

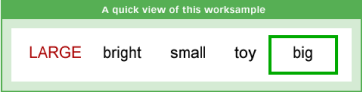

In our experience it is possible for those with low vocabularies to speed up their natural word growth with time and effort. Reading, although helpful, is not a very efficient way of learning new words on its own. To build vocabulary more quickly, you must study and learn words. The words you choose to study will have a great bearing on how successful your efforts will be. You should focus on words that are just barely above your current level of understanding. Words can be arranged in order of difficulty, from the easiest words everyone knows to the extremely difficult. People tend to learn words in this order of difficulty, stopping somewhere along the limits of their knowledge. Word learning, therefore, takes place most easily at this “frontier of knowledge,” as it is called by Johnson O’Connor. In practice, this means concentrating your vocabulary-building efforts on words you have often seen or heard, but whose precise meanings you do not know.

Words can be arranged in order of difficulty, from the easiest words everyone knows to the extremely difficult. People tend to learn words in order of difficulty, stopping somewhere along the limits of their knowledge. Word learning, therefore, takes place most easily at this “frontier of knowledge,” as it is called by Johnson O’Connor. In practice, this means concentrating your vocabulary-building efforts on words you have often seen or heard, but whose precise meanings you do not know.

Practice learning words that are just outside of your current reading level

In our experience it is possible for those with low vocabularies to speed up their natural word growth with time and effort. Reading, although helpful, is not a very efficient way of learning new words on its own. To build vocabulary more quickly, you must study and learn words. The words you choose to study will have a great bearing on how successful your efforts will be. The words you should study should be just barely above your current level of understanding.

Words can be arranged in order of difficulty, from the easiest words everyone knows to the extremely difficult. People tend to learn words in this order of difficulty, stopping somewhere along the limits of their knowledge. Word learning, therefore, takes place most easily at this “frontier of knowledge,” as it is called by Johnson O’Connor. In practice, this means concentrating your vocabulary-building efforts on words you have often seen or heard, but whose precise meanings you do not know.

For example, if you are reading an article on ships, you may come across the word “stern.” You are probably familiar with the word in a phrase like, “from stern to stern,” but you may not be clear whether it means the front or the rear of the ship. If so, this word is at your “frontier of knowledge;” if you take a few seconds to look it up it should become firmly fixed in your mind. On the other hand, you might encounter the word “capstan,” which may be totally new to you. If you were to look it up in the dictionary, you might not even understand the definition since the definition might contain words and concepts unknown to you. The solidification of a somewhat familiar word is more likely to stick in your head than a completely new word which has no real relation to other words you already know.

All these are ways that you can improve your vocabulary and expand your potential to use your aptitudes well. Rather than thinking of your aptitudes as limiting, think of the ways that you can take advantage of your gifts by improving that which you do have control over. To find out what your current vocabulary score is, we most highly recommend The Highlands Ability Battery.